Communities throughout the Arctic are reporting warmer and shorter winters, which have implications for the ice season and consequently on the access to local territories and resources by community members. Communities dependent on ice for travel and subsistence practices are experiencing unpredictable conditions which are creating challenges for travel safety and food security. Thawing permafrost and melting ice can pose health risks by hindering access to country foods, which are an important component of First Nations and Inuit diet for spiritual and nutritional well-being (Wein et al. 1996; Nuttall et al. 2005; Kuhnlein and Receveur 2007; Ford et al. 2009; Mead et al. 2010).

Travel safety is of concern as communities are experiencing high accident rates and loss of equipment. Traditional ecological knowledge (TEK) is often passed on by word of mouth and its reliability is heavily dependent on the knowledge of seasonal changes and weather patterns. Alterations in seasonal norms are impacting the nature of conventionally used ice paths and are forcing hunters to replace them with uncharted passageways. Hunters are sometimes finding themselves in dangerous situations where high risk choices are being made which may have been avoided.

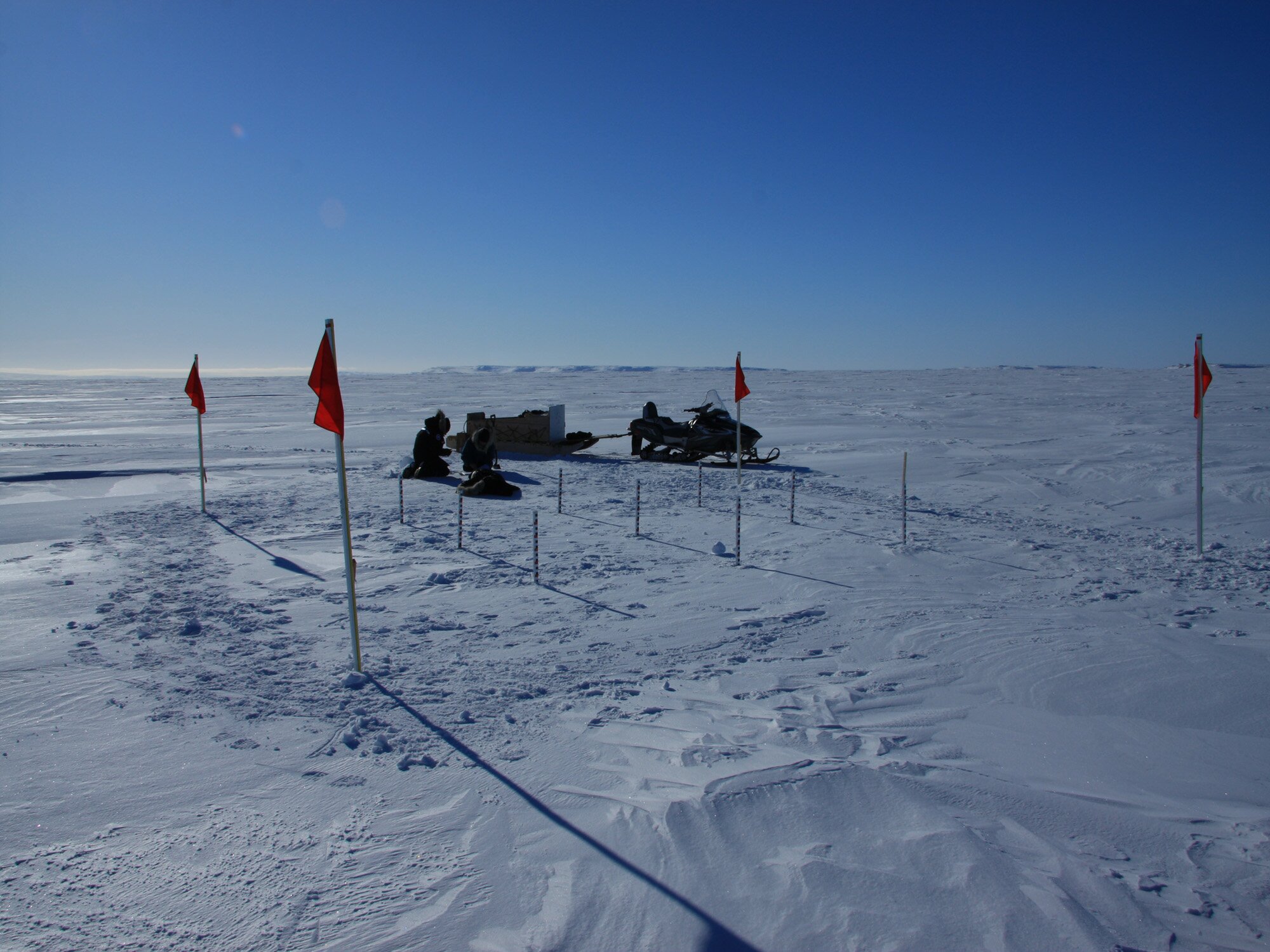

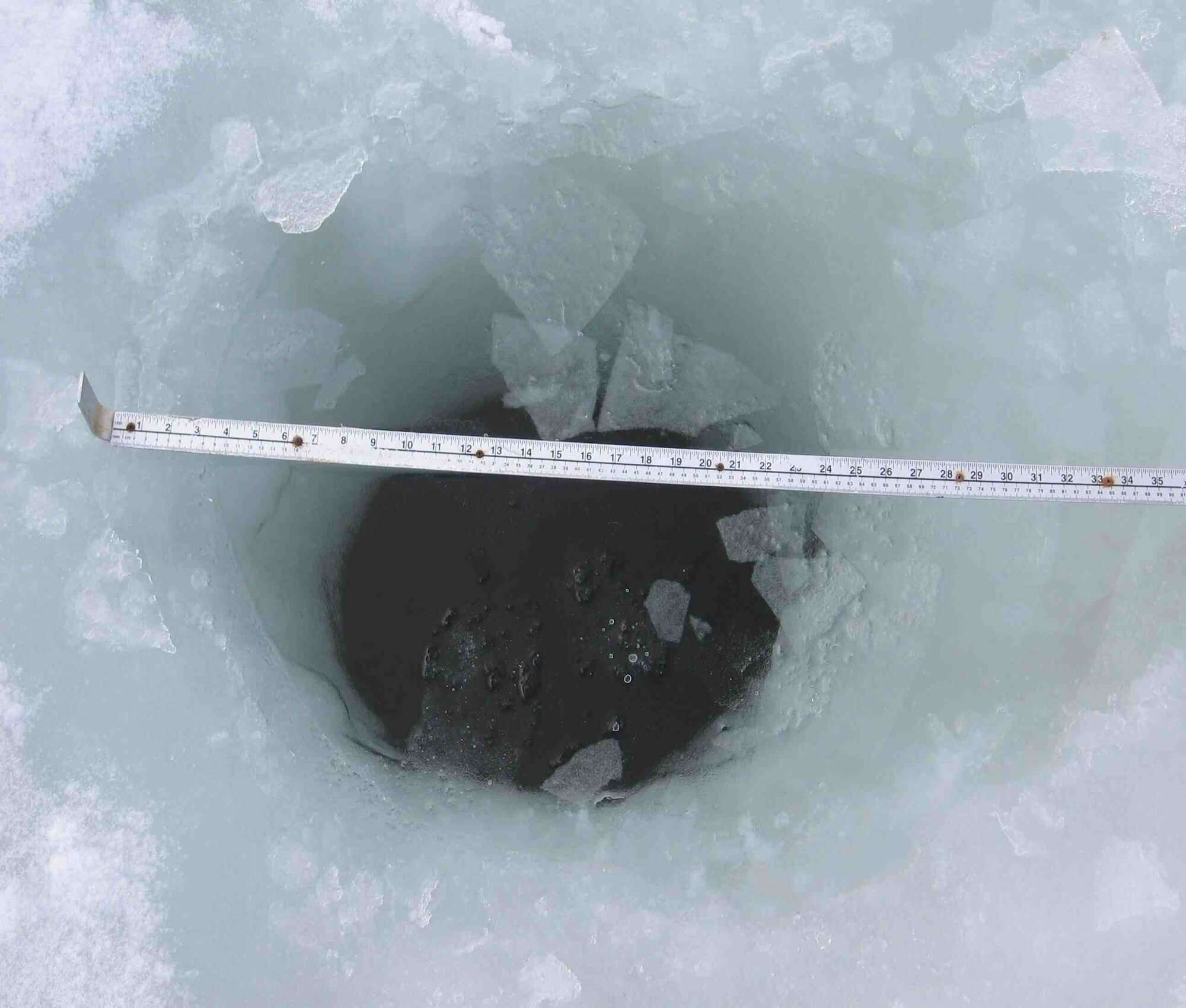

Since 2008, several Inuit communities have identified that increasing access to TEK and other knowledge systems on ice conditions could help improve travel safety and increase food security. The following stories tell of communities engaging traditional ecological knowledge (TEK) and the use of technology into ice monitoring programs.